by Dennis Crouch

What do folks think of this claim that is now pending on appeal to the Federal Circuit in Steuben Foods, Inc. v. Vidal, No. 20-1083 (Fed. Cir. 2022)?:

19. A method for automatically aseptically bottling aseptically sterilized foodstuffs comprising the steps of:

providing a plurality of bottles;

aseptically disinfecting the bottles at a rate greater than 100 bottles per minute, wherein the aseptically disinfected plurality of bottles are sterilized to a level producing at least a 6 log reduction in spore organism; and

aseptically filling the bottles with aseptically sterilized foodstuffs.

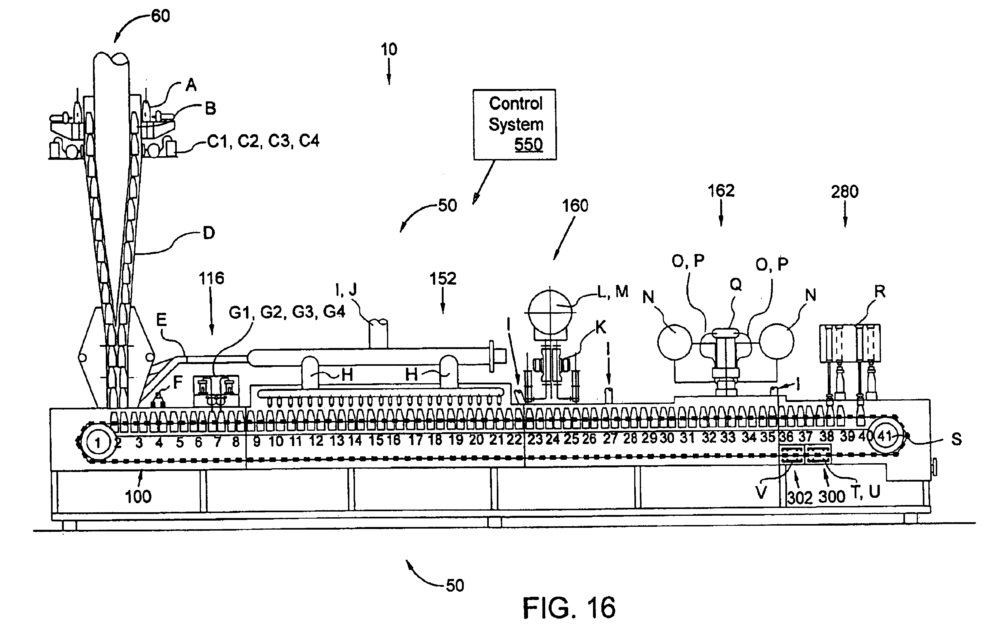

US6945013. It appears to me that the only point of novelty is the effective 100 bottles per minute feature, which is claimed here in purely functional form. I.e., it claims the result rather than how it actually happens. According to the briefing, the invention here is the “first high speed aseptic bottling system that would meet the FDA’s regulations related to aseptic packaging, which are the most stringent in the world.” According to the briefing, the real novel feature has to do with careful management of airflow “to ensure that air flows away from the bottle filling station of the aseptic bottling machine.” The drawing below shows the big vacuum tube (60) that sucks the air away. While that feature seems important, it is not actually claimed (by the broader claims being challenged).

Note that this case is IPR2014-01235, based upon an IPR petition filed in 2014. The court previously reversed the PTAB’s finding in favor of the patentee. On remand, the PTAB found the claim obvious. Nestle filed the IPR, but the parties eventually settled their dispute. The USPTO has intervened to defend its decision on appeal.

I think that the problem with this is that a functional claim (all are) should be considered in light of the accused device.

The reverse doctrine of equivalents should be used. If you device performs the functional elements in a different way and is non-obvious, then this is a defense against infringement.

Looking at a claim element absent any other solutions to the functional claim is speculation from a non-science trained judge on what the scope of a functional element is. This can not be known without knowing what other solutions may be created in the future.

As to the perils of claiming by function, Night, I should be interested in your instant reaction to the single page “squeeze” the EPO Examining Division has just imposed on American Axle. Link below. O/A of 12 August.

Either the skilled person was able at the date of the claim, and without undue experimentation, to “tune” the shaft, or undue experimentation is needed. One or the other. If the former, obvious. If the latter, claim not enabled. Examiner tells Applicant that clarification is needed.

Will that clarification come? I wonder. At the EPO, this case seems to be sailing into its patent application-swallowing Bermuda Triangle, the three vertices of which are lack of patentability over the art/ lack of clarity/ no way to amend out of it without adding matter.

Is the EPO giving Applicant a fair chance, here? Is the EPO adjudicating correctly between the interests of Applicant and those of its competitors?What say you?

link to register.epo.org

Seems like the statement you said is already assuming that all the elements in combination in American Axel were obvious over the cited references. So, this statement you quoted seem to be the final blow. What strikes me about this is here is a new driveline component being made that apparently wasn’t ever made before. So it is useful and the company wants to make them. So, new? Yes. Commercial success: Yes. Useful: Yes. But the court’s just don’t like the invention because it seems like it is obvious to them because they can understand it.

I’ve always felt that the best way to write claims is put a bit of magic in them that makes it hard for the science uneducated to understand them without some hard work. Otherwise you risk being treated like a grifter.

1. A method for manufacturing a shaft assembly of a driveline system, the driveline system further including a first driveline component and a second driveline component, the shaft assembly being adapted to transmit torque between the first driveline component and the second driveline component, the method comprising:

providing a hollow shaft member;

tuning at least one liner to attenuate at least two types of vibration transmitted through the shaft member; and

positioning the at least one liner within the shaft member such that the at least one liner is configured to damp shell mode vibrations in the shaft member by an amount that is greater than or equal to about 2%, and the at least one liner is also configured to damp bending mode vibrations in the shaft member, the at least one liner being tuned to within about ±20% of a bending mode natural frequency of the shaft assembly as installed in the driveline system.

Good of you to reply at length but two things strike me immediately. First, there is no new component. Second, if, contrary to my understanding, there is, why is there no claim to a shaft assembly including the new component. Why claim only the method?

If patentability relies on the act of tuning, then there is indefiniteness at the point of novelty, just as the EPO Examiner is currently asserting.

So, a commercial success. Yes, OK. But as to the present claim: New? Not yet. Inventive? Not yet. Definite? Not yet. Enabled? Not yet.

Drive shafts with damping liners were always “tuned”. What ever was “tuning” if not tweaking the design to reduce all modes of shaft vibration to arbitrary levels (2%, 20%??)acceptable to purchasers of the shafts?

What do I mean by tweaking the design? Are there any components of the drive shaft that make no difference at all to vibration levels? Are not all the components singing from the same song sheet? If you tweak one of them, are there not knock-on consequences for all the others?

Or are you saying that the invention is manifested in a single cylindrical liner that is “tuned” relative to not one but two or more modes of vibration? Was that ever not so?

And if you say that the invention is to reduce the number of vibration-attenuating liners down to one and one only, why then does the claim recite “at least” one (as if including more than one damper liner is within the claim)?

As I always say, patent drafting ain’t easy but with aptitude, experience and top quality coaching it can be learned. It is at its most challenging for apparently simple mechanical contrivances. When it is done competently, it deserves more respect. When incompetently, it deserves more derision.

“When incompetently, it deserves more derision.”

Much like commenting on a blog.

Except the likes of MaxDrei (and such as Greg) instead aim for “politeness” and patticake.

Just to be clear Max, I am not particularly impressed with the pinch the Examiner set up. As I believe the argument is actually tuning the one liner to the specifications recited in the claim.

So, the Examiner is effectively rejecting that argument and then saying and don’t tell me it is hard to tune it or I will give you a 112 (in US parlance.)

Night, I’m not sure that you have fully understood the “pinch” that the Applicant finds itself in, at the EPO. See my 22.1 and its reference to the Bermuda Triangle.

At the EPO, the burden of proof that a prosecution amendment is devoid of new matter rests with Applicant and the standard of proof is “beyond doubt”. That is serious. Any attempt to clarify (for example, what is meant by the seemingly arbitrary values 0f 2% and 20% that you dignify with the term “specifications” for as many shaft liners as the shaft designer chooses to use) runs the risk of adding matter.

You might not be impressed by all this, but be sure, the Examiner is definitely impressing himself now on the EPO Applicant.

Max, I get it.

My point is that the inventive step argument was the placement and tuning according to those specifications and not the how it was tuned. So, the applicant has lost that argument and the Examiner is just being slightly clever and saying there is no support for a backup argument that the tuning was non-obvious.

OK. I think I now understand your position. It is interesting to contemplate whether, with hindsight, there ever was a patentable invention here and, if so, how one would claim it. To my mind, even if one were to specify in the claim “one, and only one, liner, that single liner being tuned to more than mode of vibration”, that would not in itself be anything other than obvious given Applicant’s own admission at the EPO that there is nothing beyond conventional practice in the method they use to “tune” their liner.

>> that would not in itself be anything other than obvious given Applicant’s own admission at the EPO that there is nothing beyond conventional practice in the method they use to “tune” their liner.

I do not agree with you. I think you are right that the claim should recite either one liner or wherein each liner is tuned…

But, the non-obviousness argument was based on putting a liner in there that was so tuned. No one else had thought of that and it was an improvement. So, it was not the how to tune it but putting it in there and tune it in accordance with the parameters given.

I see your argument. And I see its potency, for a method claim, given that the burden of proof of obviousness rests with the party seeking to invalidate the claim.

But the notion that no prior art drive shaft ever had less than a plurality of vibration-damping liners is for me dubious to say the least. That the damping liners, ubiquitous in the industry, were not in any way “tuned” to mitigate vibration is not very convincing either, at least for those skilled in the art of manufacturing drive shafts that (in order to sell) don’t vibrate at unacceptable levels (say, 2% and 20%). For what other purpose than damping vibrations was the damping liner included in the conventional products?

Those are good points Max and there is no doubt a better job could have been done with the claim and spec.

But it is new from what I saw of the file wrapper there was not a 102 reference. Plus, the IPRP said it was novel.

I get your points about the “at least” causing problems.

Its a fundamentally diff. approach the EU v. the US. In the US, the law is written basically as:

“A person shall be entitled to a patent unless….”

Whereas in some Germanic states the laws are thus:

“In order to obtain a patent, an applicant must …..”

So it is two diff. approaches, impactful beyond patent law as any oldtimer knows.

It is why there is sometimes talk like ya’all been engaging in, seen it, heard it a lot. I still enjoy the intrigue of it, experiments in law.

There can be no “technical requirement” in the US w/respect to patentability, because there are no requirements. The burden is on the gov in the US to prove the invention not patentable, vs. in other juris’d’s where you have to prove patentability.

Guilty until proven innocent, or vice versa. Legal Experiments !

To Night Writer’s “Otherwise you risk being treated like a grifter.”

See link to patentlyo.com

Thanks Max for that “EPO Examining Division .. office action of 12 August on the EPO equivalent of the American Axle patent application that: “Either the skilled person was able at the date of the claim, and without undue experimentation, to “tune” the shaft, or undue experimentation is needed. One or the other. If the former, obvious. If the latter, claim not enabled.” That could and should have been a 112 rejection in the U.S. application, avoiding the patent litigation and its messy unpatentable subject matter “101” issues [as in many other such patent suits with purely functional-result main claims].

“Pure function” versus terms sounding in function and the invocation of that “Vast Middle Ground — coupled with Both the difficulty to invoke and establish an actual prima facie case under 112 coupled to the extreme ease of hand waving a 101 rejection is most likely why the actions in the US Sovereign differed from the EPO evolution.

Well yes, Paul. But look at the IPRP from the USPTO as IPEA. All 64 originally filed claims good to go forward to international issue. He who pays the piper calls the tune. Or something.

Factory Throughput being an art-recognized, results-oriented variable for increasing profit, I’d reckon a strong 103 might pop up. Method claims are sometimes “fun” to add on. Havn’t checkd and wont, did they get a patent on the machine itself ? If not, ….claiming a result is like….. claiming a cloth having a tendency to wear smooooth

Ah yes, the old wool pants that won’t get shiny as they wear case.

I always love seeing people make fools of themselves. There is a hypothetical in Lizardtech that describes this exact situation. This claim fails under both enablement and WD. Assuming it to be true that 100 bottles per minute was previously beyond the skill in the art, the claim does not fail under obviousness.

I don’t understand how anyone who is allegedly a patent attorney can be stu.pid enough to actually be confused by this – The patentee themself is asserting that prior to this invention there was no known way of bottling 100 bottles per minute. Which means at most there is now ONE known way of bottling 100 bottles per minute – the means disclosed in the specification. If, after reading the specification, one of skill knows of ONE way of doing something, does that mean they have been enabled to perform ALL ways of doing something? Of course it does not. If the patentee says that they know of no ways of doing something other than one particular way, does that mean they possess ALL ways of doing something? Of course not. The full scope of the claim is not enabled and is not described.

Lizardtech: By analogy, suppose that an inventor created a particular fuel-efficient automobile engine and described the engine in such detail in the specification that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be able to build the engine. Although the specification would meet the requirements of section 112 with respect to a claim directed to that particular engine, it would not necessarily support a broad claim to every possible type of fuel-efficient engine, no matter how different in structure or operation from the inventor’s engine. The single embodiment would support such a generic claim only if the specification would “reasonably convey to a person skilled in the art that [the inventor] had possession of the claimed subject matter at the time of filing,” Bilstad v. Wakalopulos, 386 F.3d 1116, 1125 (Fed. Cir. 2004), and would “enable one of ordinary skill to practice `the full scope of the claimed invention,'” Chiron Corp. v. Genentech, Inc., 363 F.3d 1247, 1253 (Fed. Cir. 2004), quoting In re Wright, 999 F.2d 1557, 1561 (Fed. Cir. 1993); PPG Indus., Inc. v. Guardian Indus. Corp., 75 F.3d 1558, 1564 (Fed. Cir. 1996). To hold otherwise would violate the Supreme Court’s directive that “[i]t seems to us that nothing can be more just and fair, both to the patentee and the public, than that the former should understand, and correctly describe, just what he has invented, and for what he claims a patent.” Merrill v. Yeomans, 4 Otto 568, 94 U.S. 568, 573-74, 24 L.Ed. 235 (1876); see also Phillips, 415 F.3d at 1321 (“The patent system is based on the proposition that the claims cover only the invented subject matter.”); AK Steel Corp., 344 F.3d at 1244 (“as part of the quid pro quo of the patent bargain, the applicant’s specification must enable one of ordinary skill in the art to practice the full scope of the claimed invention”). Thus, a patentee cannot always satisfy the requirements of section 112, in supporting expansive claim language, merely by clearly describing one embodiment of the thing claimed.

This claim is invalid. It’s not even up for debate. Stop embarrassing yourselves.

+1 R.G.

I enjoyed reading that polemic, Random. Patent attorneys should concentrate their efforts at claiming their client’s contribution to the art at the degree of generality that captures all the scope that is commensurate with that contribution. It really is not easy. Top class drafting does not get the acclamation and respect that it deserves.

An example I like is that of freeze branding of cattle. The value of it is that the hide is not spoiled by any burn mark. No large useful piece of hide will be rendered valueless by a burn mark in the middle.

What is the degree of generality to claim. How about claiming the result (a burn-free hide). It wasn’t obvious. Its written description is clear. Once a skilled person reads the patent they will be able to enunciate a range of branding methods other than with a branding iron chilled by liquid nitrogen as described in the patent.

At the EPO, these “claim by result” rare birds are called “problem inventions”. You know, when the contribution to the art is to recognise and specify the problem. Here, how to brand without damaging the hide. If nobody ever came to the idea to address that issue, until freeze branding was invented, there wasn’t “a problem” until the inventor “discovered” it.

As I say, scope commensurate with the contribution.

“Pioneering” inventions/patents have been historically entitled to broader protection. Did something change? Not saying that applies here. But it may. Has that changed?

Also, the full scope of THE CLAIMED INVENTION needs to be enabled. That does not mean that all means of achieving the result need to be enabled. I have had examiners get confused on this far too often.

“Pioneering” inventions/patents have been historically entitled to broader protection. Did something change? Not saying that applies here. But it may. Has that changed?

Obviously a pioneering invention is broader than an invention in a well-trod field because the latter will be constrained by 103 in a way that the former will not. But that does not change the requirements of 112.

Also, the full scope of THE CLAIMED INVENTION needs to be enabled. That does not mean that all means of achieving the result need to be enabled. I have had examiners get confused on this far too often.

Not every means, but Applicant has to demonstrate that they possess the full scope, and rarely is the full scope of something demonstrated by even a handful of embodiments.

You can invent the bow. You can even invent many types of bows. But no amount of advancements with respect to bows will yield a valid scope to the function of firing a projectile, because all your bows function under a string tension theory rather than a chemical explosion theory like the gun has. The only way to get the functional scope is to prove that the gun could not exist, which is virtually impossible to do for any function – science is inductive by nature.

Assuming it to be true that 100 bottles per minute was previously beyond the skill in the art, the claim does not fail under obviousness.

Not sure that this is correct. The ability to process 100 bottles per minute is an unexpected result that objectively demonstrates the nonobviousness of the invention. The claim scope, however, is disproportionate to the actual invention. Under those circumstances, a holding of obviousness is appropriate.

It should be a 112 rejection, not 103.

“The ablitity to process…”

Yeah, claim that. Its called a machine, or sub-combination which enables the claimed result.

Claim the machine and be happy.

Claim the result divorced from the enabling point of novelty, and ya look like an amateur !! Without enablling structure, the method is nix.

Enabling…..

You really want to use (let alone equate) “Point of Novelty” and “structure” for a method claim?

Talk about amateur….

This claim is invalid. It’s not even up for debate. Stop embarrassing yourselves.

Did you read the specification? Are there multiple ways described or only a single way? Your diatribe mentions nothing of the specification so I’m guessing you haven’t.

Plus, what does full scope mean? If the claim is non-obvious, then there are no other ways non-obvious variants to build the machine.

Did you read the specification? Are there multiple ways described or only a single way?

Multiplicity is not the standard. The standard is whether the disclosure fills the breadth of the scope. You don’t need to read the specification to know that this guy didn’t prove that there’s no other way to fill bottles, as that can’t be done. This invention wasn’t arrived at by deduction.

Random,

“fills the breadth of the scope”

Dop e, do you get that you can’t tell what this is?

>>didn’t prove that there’s no other way to fill bottles, as that can’t be done.

That is simply not part of patent law and also you don’t acknowledge it is impossible because the other ways of doing it–if there are any–haven’t been invented.

Random’s “joy at looking others make themselves look like ‘F 0 0 1 s” does not come close to his own fitting that description.

The only thing (according to “his logic” that could be patented as FULLY described and enabled would be something that could NEVER see any future improvements.

No such thing exists.

It’s turtles all the way down (in a Zeno’s paradox kind of way — there would always be “one more turtle” that would have had to have been included).

I attribute this to his inability to grasp the ladders of abstraction (he always wants to see ladders with but one rung).

You know this is our old friend Lemley trying to create another I know it when I see it test to invalidate any claim.

“[I]nability to grasp the ladders of abstraction (.. always wants to see ladders with but one rung)” seems to be part of the disagreements here. There is a legal difference between most claims with valid functional limitations versus claims where the entire claim is so functional that it claims the end result and/or “preempts” any other later invented way of achieving that result. As similarly noted, claim functionality is not a binary issue. Also, the degree to which chemical claims in particular may be validly “generically” claimed may also vary in relation to the scope of specification examples. And, a purely functional limitation in a claim element for which there is NO specification enablement at all is risking invalidity for 112(f) ambiguity.

This type of politeness is NOT really all that helpful Paul, as Random needs a thump on the noggin rather than a caress of his hand.

Further, your characterization sounds in that (now long absent) characterization that Prof. Crouch penned: the Vast Middle Ground that SHOULD safely provide for claims sounding in function (which, per the Act of 1952 are allowed — even without regard to 112(f) — which I am sure that you recognize).

You don’t need to read the specification

So you are pretty much admitting to be just shooting from the hip. Nice.

this guy didn’t prove that there’s no other way to fill bottles, as that can’t be done.

The burden of proof on the patentee? For what again?

This invention wasn’t arrived at by deduction.

What does that even mean?

“I always love seeing people make fools of themselves.”

This has to be one of the tallest peaks of Mount S.

Which machines could there be? The claims were granted so there is presumption there are no other machines that can make those 100 bottles.

So what are you talking about.

There is an interesting open question about whether CAFC’s holding in Citrix– which extends the use of 112(f) functional claiming by weakening the presumption against it– applies to method claims or not. A few lower courts have grappled with the issue. It has huge implications for software.

As currently stands, “A microcontroller configured to [do specialized function]’ would probably invoke 112(f), but “a method comprising using a processor to do specialized function” might not. I’d expect the CAFC to extend its citrix holding to method claims (step-for claiming) when it comes, but lower courts have been mixed.

Yes it is an odd situation.

In general, what is going on is Lemley is pushing “broad functional claiming” as some evil like “trolls” and “patent thickets.”

There is nothing wrong with functional claims. And again and again, look at how real people invent and how they use words and terms. Not how some paid advocates for ending the patent system consider these terms.

***I’ve posted several times on here cites to books that state that broad functional language is how inventors/engineers refer to sets of solutions.

Correct Night Writer – as I have noted now (at least twice).

In addition to your technical notes on broad functional language (which the likes of Greg “I Use My Real Name” DeLassus continues to push back against), I have also added the LEGAL aspect of elevating up the Ladders of Abstraction as an overall Best Practices in patent claim drafting (through the likes of Slusky – Invention Analysis and Claiming).

The Narrative is perpetually seeking to have “Patents be the Bad.”

“There is nothing wrong with functional claims.”

And yet below, you object to these particular claims because they don’t give enough detail.

To which a slightly more pro-functional-claim person would respond: “There are details; it operates at 100 bottles per minute!”

To me, it looks like a system designed to allow prosecutors to benefit from absurd functional claims while simultaneously deflecting any responsibility for slightly too absurd functional claims.

To allow prosecutors…

More “Wah” from the peanut gallery.

Put the anti-patent kool-aid down, Ben.

Log 6 reduction may not be trivial.

Bros I just saw some great wisdom on the internets and thought I’d share as it pertains to “the functional claiming” and “the abstract idea/natural phenom/etc. claiming” problems faced by the patent system.

And that wisdom is this:

“Clown problems require clown solutions.”

Simple, and elegant. Because that’s really what is going on here, clownery, and that is how you fight/solve such.

Could you explicate with (at least some) details?

There are multiple issues here (and as you may be aware, issues tend to have multiple sides), so it is rather unclear just what you are labeling as “clown.”

link to i.imgflip.com

Pretty funny.

Not at all helpful, so, no, not recommended.

+1

Corollary: b.s. problems require b.s. solutions.

Caught in Filter

Your comment is awaiting moderation.

August 11, 2022 at 10:02 am

or, as my pal Forrest says:

link to youtube.com

>Note that this case is IPR2014-01235, based upon an IPR petition filed in 2014.

LOL, particularly given “> 2019-05-06 Anticipated expiration”

Also interesting:

“In addition, the ’013 patent had been subject to an ongoing inter partes reexamination. See KHS USA, Inc. v. Steuben Foods, Inc., Reexam. Control No. 95/001,452. In a decision dated July 19, 2022, the Board reversed all rejections adopted by the examiner and found all 20 claims of the ’013 patent—including

claims 18 and 19 at issue in this appeal—patentable.”

Interesting prosecution history, and the Examiner’s name is not unfamiliar to those who read PTAB ex parte appeals. In fact, during prosecution the Applicant twice filed a Notice of Appeal (filing a Brief each time) and the Examiner backed down each time (allowing the case after backing down the second time). Also, the Examiner made a Restriction Requirement towards the end of the prosecution requiring the Applicant to choose between the method and the device.

Maybe they should have gone with the device claims.

The claimed invention seems obvious to me. What’s claimed as the invention is the idea of an aseptic bottling system that has a rate of greater than of 100 bottles per minute. The idea of increasing the speed of existing bottling systems is apparent from general market pressures for faster production rates. That’s often the problem with claiming a result: what’s been claimed as the invention is the idea of the result, not how to get there. Sometimes the result might be inventive, but often not.

The problem with KSR is that it encourages such analysis, under which all improvements would be unpatentable. Of course everyone wants to make an improvement. But that does not necessarily make the specific improvement obvious.

There is no problem with KSR because Jason does not accurately apply it. What KSR says is that market forces can prompt variations and if a variation *can be implemented* then the claims are likely obvious. Here the argument for patentability is that 100 bottles was desired (of course it is, more throughput is always desired) but was outside of the enabled skill. That doesn’t run afoul of KSR.

Reread my comment again. I said it “encourages” such analysis. Thanks.

99 bottles of aseptically sterilized foodstuffs on the wall…

My chuckle for the day — thanks k.

That claim is total garbage. Thanks for the laughs!

Heckuva job, PTO. Wow.

The functional garbage can (and should) be ignored and then you are left with a claim that is either anticipated or laughably obvious.

I’m curious: What does the spec teach as the improvement this “invention” makes over the prior art? Nothing?

^^^ and that is precisely the mindless Narrative aimed for with this type of Tr011, click-bait type of post.

‘Wah, patents be the bad, they are all grifters’

Claims distinguish the invention over the prior art. Specification enables practice of invention.

You talk about a”Functional Claiming Question.” What is the problem? Is it about enablement? About indefiniteness?

Couch your question as it pertains to a particular statutory requirement.

Good analysis.

It’s plainly a 112 problem with the claims which recite desired results but do not describe the steps or machines that distinguish the process from the prior art.

There are multiple ways to address the problem of functional claiming. As with many spectacular failures, the claim is so bad that numerous aspects of the patent statute are potentially offended depending on how you want to slice it.

It’s plainly a type of click-bait Tr011ing question (as Wt astutely points out in a rather polite manner).

“Claims distinguish the invention over the prior art.”

No, claims “particularly point out” the invention.

B-b-b-but ‘claims are supposed to be Engineering level details’

/S